sea turtles

These great threatened migratory birds!

Généralité

Threats and conservation status:

Life cycle

Sea turtles have a well-established life cycle that Man was only able to penetrate quite late. Since the 1970s that we have been studying them, many mysteries about these fascinating migrants have been discovered. However, the juvenile cycle, the first 3 years of their offshore life, still remains an enigma.

Egg laying has been the most studied due to the ease of approach on the beaches. Technology then allowed us to follow the migrations of these reptiles using Argos beacons. We now know that certain species such as the green turtle, the Leatherback turtle or the Loggerhead turtle can travel thousands of kilometres, cross entire oceans, to go to their nesting sites and/or reach their feeding site. Advances in terms of genetic studies have allowed us to learn more about the different populations of the same species. And we especially know that in the end, 1 in 1000 survives to reach adulthood. The diagram opposite speaks for itself!

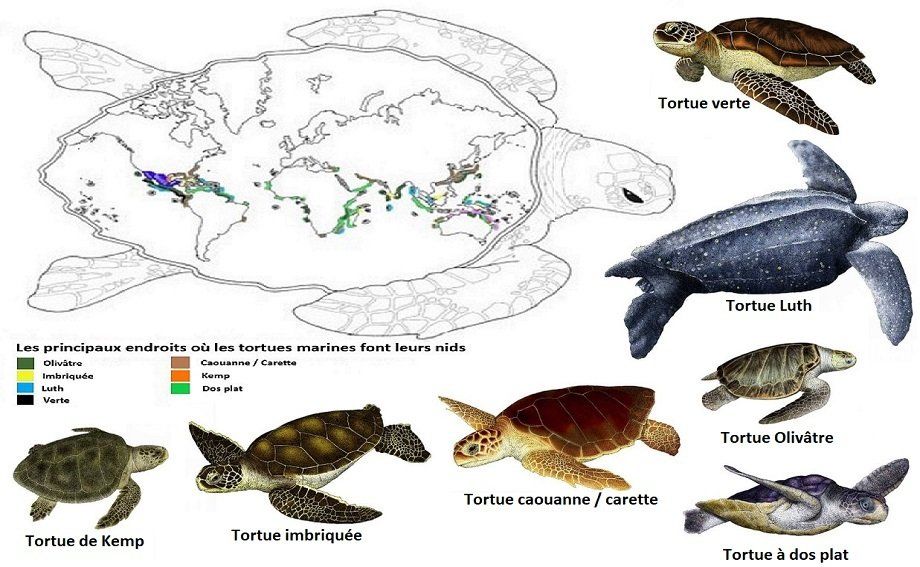

How to recognize

different species?

It is not easy for the untrained eye to differentiate the species of turtles. In their environment, with the depths the colors can vary, moving animals can quickly escape you. Even experienced divers can be wrong! However, there are some unstoppable keys, physical particularities, which will allow you to identify the species you have in front of your eyes!

food

Most of the time, we think sea turtles only eat jellyfish. This is partly true, but not all species eat the same thing. They have a much more varied diet, adapted to their places of life. Moreover, they are all morphologically adapted to a certain type of food with a beak specific to each species. The largest and most emblematic leatherback turtle actually consumes jellyfish exclusively with a beak and a trachea adapted to this food, comprising species of thorns so that the stinging tentacles of the jellyfish do not hurt it. Other species like the loggerhead turtle, olive ridley, Kemp are omnivores and eat fish as well as crustaceans and molluscs , with a huge parrot beak to crack the shells. The hawksbill turtle eats several varieties of sponges which makes its flesh poisonous and unfit for consumption. Its beak is pointed in order to reach the sponges in the interstices of the corals. The green sea turtle changes its diet over the course of its life. . First of all carnivorous in the juvenile stage, it becomes herbivorous in adulthood , consuming algae and other sea grasses. This diet will give it a green fat, from which it gets its name. Each species therefore has its ecological role to play.

Photos: S. Goutenègre.

Sexual dimorphism

Comment différencier les deux sexes? Du premier coup d’œil ce n'est pas évident, et pourtant il y a bien deux caractéristiques physiques qui différencies mâle et femelle! Tout d'abord la queue : à l'âge adulte le mâle en possède une plus longue que la femelle. Elle dépasse les nageoires arrière chez le mâle. Il y a ensuite les griffes : Les tortues possèdent une ou deux paires de griffes (en fonction de l'espèce) sur les nageoires avant. Le mâle en possède des incurvées et plus longues que la femelle afin de pouvoir agripper cette dernière pendant l'accouplement en mer. Pour finir, les mâles de certaines espèces, comme la tortue verte, peuvent être légèrement plus petits que la femelle.

The reproduction

Sexual maturity is reached very late in turtles, between 15 and 30 years old. for some. Mating follows a long migration where large aggregations of turtles meet off the nesting sites. Several males will then harass a female to try to cling to her using their claws on the front fins. The act is quite perilous for the female because she has to come to the surface to breathe with her suitor weighing more than 100 kg on her back! Several males can fertilize the same female, allowing genetic mixing. The female is able to store the sperm of the males for several years to "self-fertilize". The female goes up to the beach to lay eggs, often at the place where she was born, at night to avoid sunburn and predators. The spawning cycle is generally every 15 days in the green turtle and up to 14 times in the same season . It goes up the beach on the edge of the vegetation in order to find a place under cover of it. She can spend several hours crawling and trying to dig several nests before finding the right place. Using its rear fins, she digs a well at least 80 cm deep to lay between 80 and 100 eggs , which she will cover and pack down carefully. This operation can take from 40 minutes to 1h30. The whole egg-laying process, from climbing back to the ocean, can take turtles up to 4 hours. It can stay a whole night on the beach and only return to the water in the early morning. Next she will return to the ocean to return to this place 15 days later, to lay another 80 to 100 eggs . On average, a female reproduces approximately every 2 years. Sea turtles have no maternal instincts and do not care for their hatching offspring. They will already have gone far to feed, leaving the newborns to their fate!

Incubation lasts an average of 2 months . The babies will be born at the bottom of the nest and will take up to 2 days to rise to the surface , waiting for the coolest moment, at night, to reach the ocean.

As for the males, they do not come ashore, they will return to their feeding sites at the end of the breeding season. On the other hand, in the green turtle, outside the breeding season, both sexes can be seen washing up on the beaches to warm up, as observed in Hawaii.

Photos/ videos: S. Goutenegre. Green turtle clutches and newborns in French Polynesia.

Cold-blooded animals?

Reptiles are known to be cold-blooded... not exactly. They don't have a cold blood to speak of. They can regulate their body temperature by basking in the sun. The same goes for sea turtles. This is why most species live in tropical or sub-tropical waters. In too cold water they risk hypothermia. Sea turtles are often found stranded and weakened on the Atlantic coast of our coasts. Leatherback turtles or loggerhead turtles, carried by the Gulf Stream, find their way into our cool waters and can die from it. On the other hand, when climbing on the beaches for egg laying, too long exposure to the sun risks killing them. They therefore prefer the night to lay eggs.

Photos (S. Goutenègre): Adult green turtles in Polynesia.

La température détermine le sexe!

Toujours une histoire de chaleur...

Chez les tortues marines, comme chez d'autres reptiles, la détermination du sexe n'est pas programmée à l'avance. Elle intervient pendant l'incubation grâce aux températures du nid! En effet, il existe une température pivot de 29° C qui va déterminer le sexe. Plus il fait chaud, plus cela produira de femelles, plus il fait frais, plus il y aura de mâles. La température dans la chambre d'incubation n'est pas la même à toutes les profondeurs, cela réparti ainsi l'équilibre des sexes.

Il faut savoir que l’œuf n'a pas une coquille mais une membrane souple qui permet un échange gazeux avec l'embryon.

D'où l'importance pour les femelles de trouver souvent de la végétation pour protéger les nids des fortes chaleurs. L'hygrométrie a aussi son importance pendant l'incubation.

A l'heure du réchauffement climatique, ces bouleversements météorologiques ont un impact direct sur les populations de tortues marines.

Photos: S. Goutenègre. Oeufs et bébés tortues verte à Bora Bora.

Hatching, the great epic for survival...

Incubation is not easy and the embryos are not safe from predators, long before they are born. As soon as the females left for the ocean, the eggs are already coveted by wild pigs, dogs, birds, monitor lizards, jaguars and the men who will plunder the nests. On certain beaches over-frequented by turtles, such as the Olivâtre, some females, while digging their nests, destroy those laid by their congeners...

At the end of 2 months of incubation and a variable hatching rate (between 30% for the lute and 90% for the olive tree), the newborns will be born at the same time, in order to be able to rise to the surface by a pushing phenomenon, which can take them until two days to reach the surface! During incubation, a gas exchange will take place between the sand and the embryo. At their birth, the baby turtles will chemically imbibe the texture of the sand and "photograph" the beach so that they can come and reproduce there in turn... up to 30 years later! They will favor the night for milder temperatures and thus avoid predators. When they leave, an incalculable number of terrestrial, winged and marine predators await them... Seabirds, crabs, monitor lizards, stray dogs... Once the water is reached, it's the turn of the biggest fish such as tuna, trevally, barracuda and other sharks that invite themselves to the feast. Eventually, 1 in 1000 will reach adulthood. The phenomenon of mass spawning responds to these losses, nature is well done! The baby turtles head straight for the horizon line, attracted by the reflections of the Moon. Once the ocean is reached, the survivors will begin what is called a frantic swim and swim continuously out to sea for 24 hours. The first days, the little turtles do not feed because they have reserves with their yolk sac, their umbilical slit not being completely closed. Light as a feather, they are unable to dive , they float and therefore continue to be prey!

Light pollution can be a real problem for small turtles who think they are following the reflection of the moon on the sea. They will rather go towards the light source which disorients them...

During your travels, if you have to witness the laying or birth of turtles, use a headlamp with red light, the animals are less sensitive to it. Refrain from using high-powered flashes and lamps...

Years of wandering offshore will follow, often sheltered by floating debris or seaweed. It is not uncommon to find baby Loggerhead Sea Turtles floating in Sargassum mats. We have very little information on the biology of juveniles, this is called the lost years . They will reappear around the age of three, along the coasts or coral reefs.

Freediving champions!

Sea turtles are reptiles, they have lungs. They are able to stay longer than 30 min snorkeling and diving to almost 100 m depth, the overall champion being the leatherback turtle. At night, they don't come ashore to sleep! They have their favorite cavity or coral where they settle to sleep. While sleeping, they slow down their metabolism which allows them to come back to the surface less often during their sleep. They can sleep for more than an hour without coming to the surface. Their plastron (belly) is flexible, which in particular makes it possible to compensate for underwater pressure. Their cooler blood than mammals requires less oxygen. Thus in apnea, during their sleep, the vital organs are primarily "oxygenated". In particular, the swim bladder plays an important role in controlling buoyancy/diving.

Unparalleled migrants!

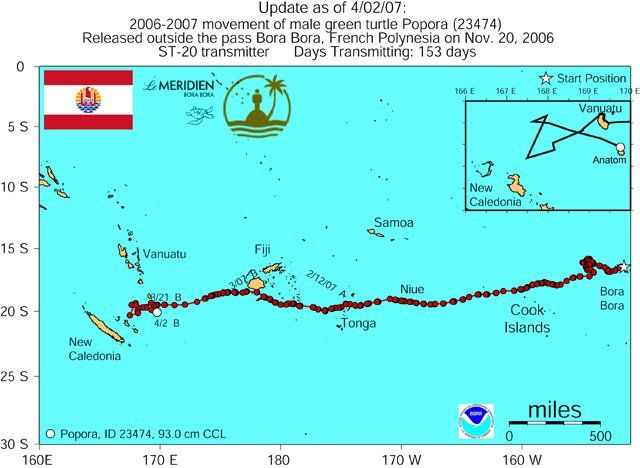

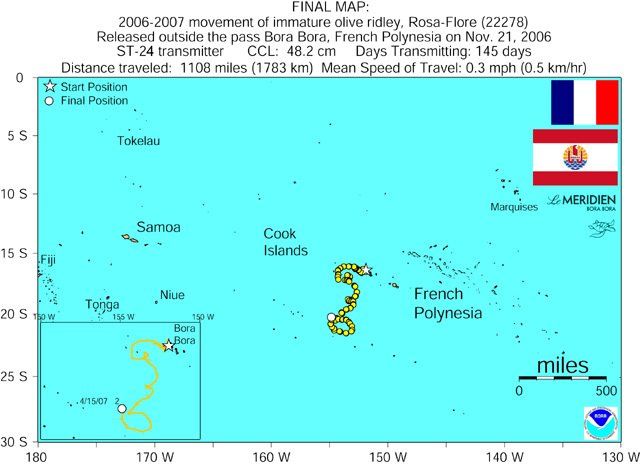

Sea turtles are present in almost all oceans. Their anatomy evolved in the Cretaceous to make them animals cut out for the open sea and long distances. Their powerful fins allow them to reach top speeds of up to 35 km/h. Following satellite monitoring carried out over the past 20 years, we now know that they can cross entire oceans to reach their breeding or feeding. Here is the example of the green turtle that we have been studying for years in French Polynesia.

Egg-laying sites far from feeding sites

A 5,000 km migration in the South Pacific!

We will take here the example of the green turtle that we have been studying since 2005 in French Polynesia, which is a great migrator. The same is true for other species that travel thousands of kilometers and cross the oceans: The leatherback that lays and breeds in French Guiana crosses the entire Atlantic using the Golf Stream to sometimes end up on our Atlantic coasts to eat jellyfish. As for the Loggerhead turtle, we know that it crosses the entire North Pacific, from Japan to the Californian coast. Holy travellers!

Sea turtles, being programmed to return to lay their eggs where they were born, are inexorably driven by the magnetic fields and sea currents that guide them. In effect, they have a kind of compass in the brain that keeps them on course . They can head for the stars or the moon and often migrate in groups. L Adult turtles are able to store fat and hardly eat during their migrations.

The example of the green sea turtle in the South Pacific is typical. In adulthood, this species which is born in Polynesia becomes herbivorous. Polynesia unfortunately does not offer seaweed resources, which forces turtles to migrate to find their food. It's not a risky quest but a program that will lead them thousands of miles away to feed themselves. We have followed and studied the routes of 5 male and female green turtles in 2006 which taught us the migratory route in the South Pacific and the distances traveled by these reptiles . The president of the association, Sébastien Goutenègre, took part in this operation and equipped 5 adult green turtles and 1 sub-adult olive ridley turtle with Argos beacons under the aegis of Diren Polynésie, an American team from the NOAA agency led by Mr. George Balazs and Mr. Lui Bell from Samoas, under the Pacific Regional Environment Program (SPREP). Released off Bora Bora in November 2006, one of the males was followed for almost 5 months across different states in the South Pacific, to reach its feeding ground in New Caledonia, nearly 5,000 km from Bora Bora . Other turtles were stopped (it is assumed killed) in Fiji which is 3,000 km from their starting point . On the map below, we clearly see the migratory line which does not deviate, which confirms the use of magnetic fields. Each point corresponds to the satellite reading when the turtle comes to the surface to breathe. These data were a discovery which aimed to federate the States they cross, in order to coordinate better management of their conservation. You must know that culturally speaking, all peoples of the South Pacific consume turtles . This means that they have many obstacles to overcome before coming to lay eggs and the same to go back to feeding! Much remains to be done in terms of educating the population for the preservation of these migratory species.

The turtles spend the year on their feeding grounds to replenish their stock of fat. Females begin this migration every two years.

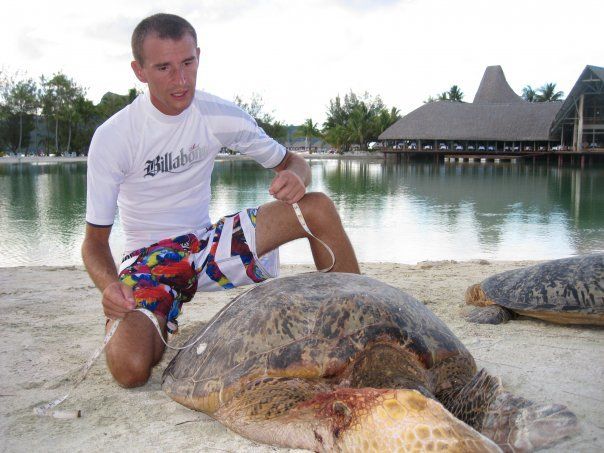

Pictures (S. Goutenègre) : Placing an Argos beacon on an adult green turtle in 2006, in Bora Bora.

Tagging and identifying sea turtles

For conservation and population monitoring purposes, it is necessary to mark and identify sea turtles. Indeed, these great migrators travel in all oceans and can be ringed in French Guiana, for example for the leatherback turtle, and find the same individual who died 15 years later in West Africa or France. This makes it possible to study the routes and follow an individual throughout his life. There are mainly two ways to mark and identify turtles:

- By closed metal ring (in titanium or stainless steel), fixed with a specific clamp. There are several protocols depending on the geographical area (in the South Pacific turtles are ringed on the right front flipper for juveniles, and on both front flippers for adults). The disadvantage of this marking is that the animal may lose its ring during its life. Indeed, turtles living on coral reefs can tear off the rings while exploring or sleeping in the reefs.

- By electronic chip (PIT tag) . This method allows permanent marking because the animal will not be able to lose the chip during its life. The electronic chip must be able to be easily read by a chip reader (if it is placed in the neck, it can slip under the shell and will therefore be undetectable...). In the South Pacific, the protocol is to introduce the chip in the top of the rear fin. The chip, which has a unique identification number, is entered into a database with the biometric measurements of the animal, accessible to other biologists and authorities in charge of conservation programs. It is introduced under the skin using a "pistol", a painless operation for the animal.

Photos (S. Goutenègre): Installation of metal rings and microchips on turtles by Sébastien Goutenègre in Polynesia.

Health monitoring

Afin de permettre un suivi de croissance et une bonne santé générale de l'animal, il est possible de prendre plusieurs mesures biométriques afin de les transmettre aux autorités en charge des plans de conservation. Mesures de la carapace, pesée, état de l'engraissement, vérification du plastron, état générale, marquage et identification. Ces examens sont pratiqués uniquement par des professionnels, les tortues marines étant vectrices de zoonoses. Les tortues marines, notamment les tortues vertes, peuvent développer un virus souvent incurable, la Fibropapilomatose. Fréquemment observée sur l'archipel d'Hawaï, les tortues développent des tumeurs sur tout le corps et dans les muqueuses. Ces données sont enregistrées dans des bases de données, avec leur numéro de bague ou de puce électronique, afin que d'autres biologistes puissent les consulter si elles sont retrouvées à des milliers de kilomètres. Si vous trouvez une tortue échouée morte ou vivante, ne la touchez pas! Contactez la Mairie de la commune, ou la gendarmerie, ou le centre de soin le plus proche. En Métropole, sur la façade Atlantique, plusieurs centres prennent en charge les tortues en détresses, comme le centre de soin de l'aquarium de La Rochelle ou l'aquarium de Biarritz. En Méditerranée, le Cestmed, au Grau-Du-Roi ou le centre du musée océanographique de Monaco.

The threats...

The 7 species of sea turtles are all threatened by human activity. There are many threats to these reptiles. We contribute to their decline through the urbanization of the coastline, the plastic pollution of the oceans and beaches, poaching for the consumption of their flesh or for the use of their scales, accidental catches in fishing nets, and global warming. climate that influences the sex of turtles.

WORK TOGETHER

The 4 main threats to sea turtles:

01

Coastal urbanization

The human population explosion and the development of mass tourism over the past 30 years have considerably modified the coasts. A turtle born 30 years ago would surely not recognize its beach today. The concreting of the coasts and light pollution promote the disappearance of sea turtles. Turtles returning to lay eggs where they were born then find themselves without a nesting site, a region is thus depopulated from its fauna.

02

Pollution des océans et des plages

The explosion in the use of plastic in all its forms since the 1970s has contributed to the decline of marine and avian species through the ingestion of bags, corks and other micro plastics. The beaches are not free from this pollution: ropes, tires, which can trap adult turtles or babies. Even on the most remote islands of the planet there is plastic pollution. Oil spills do not spare turtles.

03

Accidental fishing/ driftnets

Driftnets and other incidental fishing are the cause of thousands of turtle deaths on the planet. The ingestion of hooks also causes great damage. Over the past 20 years, efforts have been made in the fisheries to avoid these catches. Sea turtles pay a heavy price to meet our consumption of fish and shrimp.

04

Poaching

Poaching remains a scourge for sea turtles. They are coveted everywhere for their flesh, their eggs, or their scales used as raw material for making various objects (comb, bezel), their leather is also used. Despite their protection, some populations of sea turtles are decimated by poaching under the guise of customary tradition.

Photos: S. Goutenègre

Poaching in French Polynesia

In many countries, sea turtles have always been part of the culture. We eat the flesh or the eggs for different reasons. The latter were on the verge of extinction in several regions, which forced the authorities and CITES in the 1970s to regulate these practices. This demand for turtles has led to often uncontrolled poaching... Here we will take the example of Polynesia, French territory, and the consumption of green turtle meat. We have 10 years of experience in the fight against poaching in this region.

Sacrifice a species for tradition?

Pour bien comprendre la problématique du braconnage en Polynésie, il faut d'abord connaître le lien fort qui lie les polynésiens à la tortue. Depuis la nuit des temps, la tortue marine est un animal sacré et fait partie de la culture polynésienne. Elle est d'ailleurs l'emblème royale à Bora Bora. Elles sont représentées un peu partout dans l'artisanat : le tatouage, la sculpture sur bois ou sur nacre, les pétroglyphes... Autrefois, les hauts dignitaires avaient le privilège de manger ce met sacré afin de s'approprier le mana de l'animal, son pouvoir spirituel. Ce met réservé à l'élite royale était tabu (mot polynésien signifiant interdit) pour le reste de la population. Cette pratique était à l'époque sans grande conséquence pour les populations de tortues car les prélèvements étaient anecdotiques et limités. Cette tradition ancestrale s'est interrompue à l'arrivée des missionnaires et fut interdite, tout comme la pratique de la langue polynésienne, les tatouages et la danse. La disparition successive des différents chefs et de la famille royale Pomare a eu pour conséquence de "démocratiser" cette pratique et ce tabu fut levé par revendication identitaire et culturelle par la plus large population. Depuis les années 90, les polynésiens se sont réappropriés leur culture riche et variée, proche de la nature, remettant au goût du jour la pratique de la danse, du tatouage mais aussi la consommation de chair de tortue. Cependant, dans cette revendication identitaire, les tortues font depuis les années 90 l'objet de trafic à des fins mercantiles et non dans le respect des traditions. La différence avec le temps des Rois, est qu'elles sont largement menacées d'extinction car braconnées à n'importe quel moment de l'année, sans distinction de taille. Ce qui reste problématique pour la survie de ces espèces. En effet, une tortue verte atteint sa maturité sexuelle pas avant l'âge de 25 à 30 ans, sachant que 1 bébé sur 1000 survit... nous leur laissons peu de chance! Elles sont totalement protégées au niveau internationale par la Convention de Washington, et donc en Polynésie française également. Doit on sacrifier une espèce pour une question identitaire? Quel héritage et quel patrimoine naturel les polynésiens veulent ils laisser aux prochaines générations? A cette allure, si il n'y a pas une prise de conscience globale de la population, nous risquons de ne plus voir de tortues dans nos lagons. Certaines adultes ont déjà disparues de quelques îles comme à Bora Bora.

Photos : Tortues verte adultes issues du braconnage à Bora Bora. Ici Sébastien Goutenègre, président de l'association, soigne une tortue adulte harponnée à la nageoire et prend des mesures biométriques.

Illustration of poaching in Polynesia

Poaching is difficult to quantify in Polynesia due to the area of the Territory. However, we know that this poaching is mainly concentrated on the Iles-Sous-Le-Vent in the Society Archipelago, where the greatest demand for turtle meat is found. Adults of both sexes are poached mainly on the egg-laying sites of the atolls of Scilly (although classified as a reserve) and the atoll of Mopelia. The most common poaching method is called "by buoy". The animals are harpooned at sea, on the front flipper, when they come to the surface to breathe. The harpoon is connected to a buoy which prevents the turtle from diving. She is hoisted onto the boat, tied up then held on the back (which is not the most comfortable position). They are not killed immediately and can remain on their backs for days. They will be killed at the time of consumption or cut up and packaged in sachets for resale. The major problem is that the females are captured before they can spawn, which destroys their chance of reproduction. and ultimately sacrifice a generation of turtles. The authorities in charge of the protection of protected species and regulations are the customs service and the gendarmerie brigades on the islands. The latter lack the means to cover this territory. At the administrative level, the Diren of the Polynesian government set up a sea turtle conservation program in the 1990s and endeavors to take measures so that the Polynesian population becomes aware of the issue. This is still a very thorny and sensitive subject that is far from being resolved... The education and awareness of younger generations seems to be bearing fruit, which is encouraging for the future of sea turtles in Polynesia and more broadly in the South Pacific.

Report in a 2012 issue of Thalassa on turtle poaching in Polynesia. The captured turtles are juveniles, far from having reached their adult size. This report illustrates well the complex dilemma between tradition and the protection of endangered species.

Conservation action in

response to poaching

It is sometimes difficult to stem poaching. However, there may be a solution to compensate for the loss of females. Incubate eggs from deceased poached females. This action gives a chance to incubate those eggs that otherwise would have been lost. Thus, this action makes the births of turtles continue, which will return to these same egg-laying sites. A way to repopulate the sites within 30 years.

Incubate eggs from poached females!

The intensive poaching of turtles for their meat seriously threatens certain species, such as the green turtle. One of the solutions in response to this poaching could be to incubate eggs from killed females. This conservation action was established in Polynesia at the Le Méridien Bora Bora center and implemented by Sébastien Goutenègre, president of the association, between 2006 and 2011, following the numerous poached females on the island of Bora Bora. The population having become aware of the problem, spontaneously brought back eggs taken from the bodies of poached females who were about to lay. The idea is very simple, incubate these eggs so that the female does not die in vain and give birth to other generations of turtles. Indeed, the females coming to lay at intervals of 15 days on their spawning site, always have fertilized eggs in reserve in their oviduct. It is then necessary to act quickly, because it is a race against time to avoid losing the eggs, too long exposed to the open air.

The operation consists of recreating a turtle's nest, in situ , with the same environmental characteristics. After two months of incubation (natural, without temperature control), there is between 30% and 60% hatching success. The goal is to start raising these babies until the juvenile stage (2 to 3 years old) to give them a better chance of survival, before releasing them. UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES IS IT ABOUT MOVING NESTS!

Photos (S. Goutenègre): R reconstructions of nests with eggs from deceased females.

Réchauffement climatique:

les tortues les premières victimes...

This famous ongoing global warming is already having consequences for sea turtle populations and threatening them directly. Indeed, the increase in cyclones, tropical depressions and rising waters threaten their nesting sites or destroy them. Beach erosion threatens nests. The predicted increase in temperatures also influences future generations of turtles whose sex is determined by heat.

Apocalypse in the tropics...

La multiplication et fréquences des catastrophes naturelles sous les tropiques ces dernières années sont bien réelles. Le réchauffement climatique accentue les phénomènes de cyclones, dépressions tropicales qui ont pour conséquences de submerger les îles et atolls comme en Polynésie. Ces atolls ne sont pas à plus d'1. 50 à 2 m au dessus du niveau de la mer. Les fortes houles et autres montées des eaux ont vite fait de submerger et détruire une plage. Nous en avons été témoins en 2010 à Bora Bora avec le cyclone Oli qui avait fait beaucoup de dégâts en Polynésie. Notons que le cyclone ravage aussi bien en surface que sous l'eau! Les barrières récifales sont littéralement balayées, laissant un paysage de désolation sous-marin... Tout ces phénomènes climatiques ont donc des conséquences sur la vie des tortues marines. Tout d'abord, la disparition ou destruction de leurs sites de pontes par submersion et/ ou par l'érosion.

Les experts climatiques annoncent un réchauffement des températures qui aura également un impact sur les futures populations de tortues marines dans le monde. En effet, comme le sexe chez ces reptiles est déterminé par la chaleur, il risque d'y avoir de fortes disparités sur les populations de mâles et femelles.

Photos (S. Goutenègre): Lagons et motu en Polynésie à la merci de la montée des eaux.

Passage du cyclone Oli à Bora Bora en 2010, avec submersion des plages et destruction des coraux.

08 Juin,

journée de l'océan!

Célébrons les tortues et l'ensemble

de la faune marine.

The oceans and forests are the two lungs of our planet! Human impacts on the oceans are increasingly felt, threatening a large number of marine species. Turtles and cetaceans are the first victims: plastics (especially micro plastics) have invaded their habitats. Accidental fishing kills millions of animals a year, ocean acidity and warming kills corals, poaching is decimating turtle populations, boat collisions kill thousands of animals, sea level rises threaten turtle nesting sites...

Together, let's reverse the trend!